Projects

Gone Jellyballing: Gelatinous Life Sciences in the American South (ongoing since 2018)

Gone Jellyballing is my PhD project. It explores the hidden but widespread role of gelatine and collagen—proteins derived from animal connective tissues—in our daily lives. These substances are used in everything from photography and food to cosmetics and medicine, but they are often overlooked. Combining geography, art, and science, my practice-related research investigates the life and science behind these materials, focussing on the United States’ only operational jellyfish fishery in Darien, GA.

Gelatine and collagen have a long history, from glue in ancient Egypt to gelatine-based capsules in pharmacies and their contemporary formulation in beauty products and photography. Despite their broad uses, little social science research has been conducted. My research has for the last several years traced global gelatine and collagen markets, following their transition from ‘byproduct’ to essential elements of (post)modernity. It considers gelatine and collagen as not just physical substances but as part of our overlapping social, ecological, and economic systems.

Situating the cannonball jellyfish fishery located on Georgia’s coast as a case study, the project examines a university food science biotechnology initiative extracting jellyfish collagen, whose partial goal is to boost the American South Atlantic’s socioeconomics. It is framed by the University of Georgia’s Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant between landscape (coastline), commodity (companion jellyfish), and creativity (photography).

Jellyfish are particularly interesting to contend with for gelatine and collagen’s material ‘thing’ liveliness, and gelatinous zooplankton’s quality of being alive. Gone Jellyballing traces the rise of gelatine and collagen industries in the ‘West’, explores jellyfish ecologies in the American South Atlantic, works to understand the relationships humans form with jellyfish in domesticity, and creates artistic work using jellyfish-derived gelatine to highlight these unseen connections.

On Jellyfish On Jellyfish, 2025

Jellyfish Photo Booth, 2025

Jellyfish Photo Booth is a participatory and socially engaged art project. First presented at Darien, Georgia, USA's annual Blessing of the Fleet in 2025, the project brings together myself, a food scientist (Peter Chiarelli), and aquaculturist-biologist-hobbyist-all-things-jellyfish (Travis Brandwood) to holistically engage local residents and visitors from further afield about the United States' currently only operational jellyfish fishery.

The project features collagen-derived materials and products produced by Chiarelli, lab-reared Atlantic cannonball jellyfish (stomolophus meleagris aka Species 1) by Brandwood, and a cannonball jellyfish-based silver gelatine photographic emulsion produced by myself using Chiarelli's material. It also includes research materials and other objects pertinent to the construction of a more-than-human gelatinous coast. Attendees were invited to engage with our stand and have their portrait taken using the emulsion on paper negatives in a large format 4x5 field camera.

This project forms part of my PhD thesis's final empirical chapter and is a practice-based attempt to engage the public with Georgia's coastal ecologies while raising awareness about the importance/endurance of the jellyfish fishery and its stakeholders' desire to increase production sustainably. Jellyfish Photo Booth was in part funded by a Queen Mary University of London Festival Funnel Funding grant, with further logistical support from Golden Island International and The Jellyfish Compendium. A further thanks to Peter Chiarelli for conducting a material transfer authorisation between the University of Georgia and Queen Mary University of London, which facilitated my production of the experimental photographic emulsion; as well as to the Darien-McIntosh Chamber of Commerce for its support and in-kind match funding.

Cabinet Cultures (ongoing since 2023, with Giulia Carabelli)

Cabinet Cultures: East London Ecologies, 2024 (with Giulia Carabelli, Nirit Binyamini Ben-Meir, Erin Robinson, Patrick Healey, and Alexandre Duponcheele)

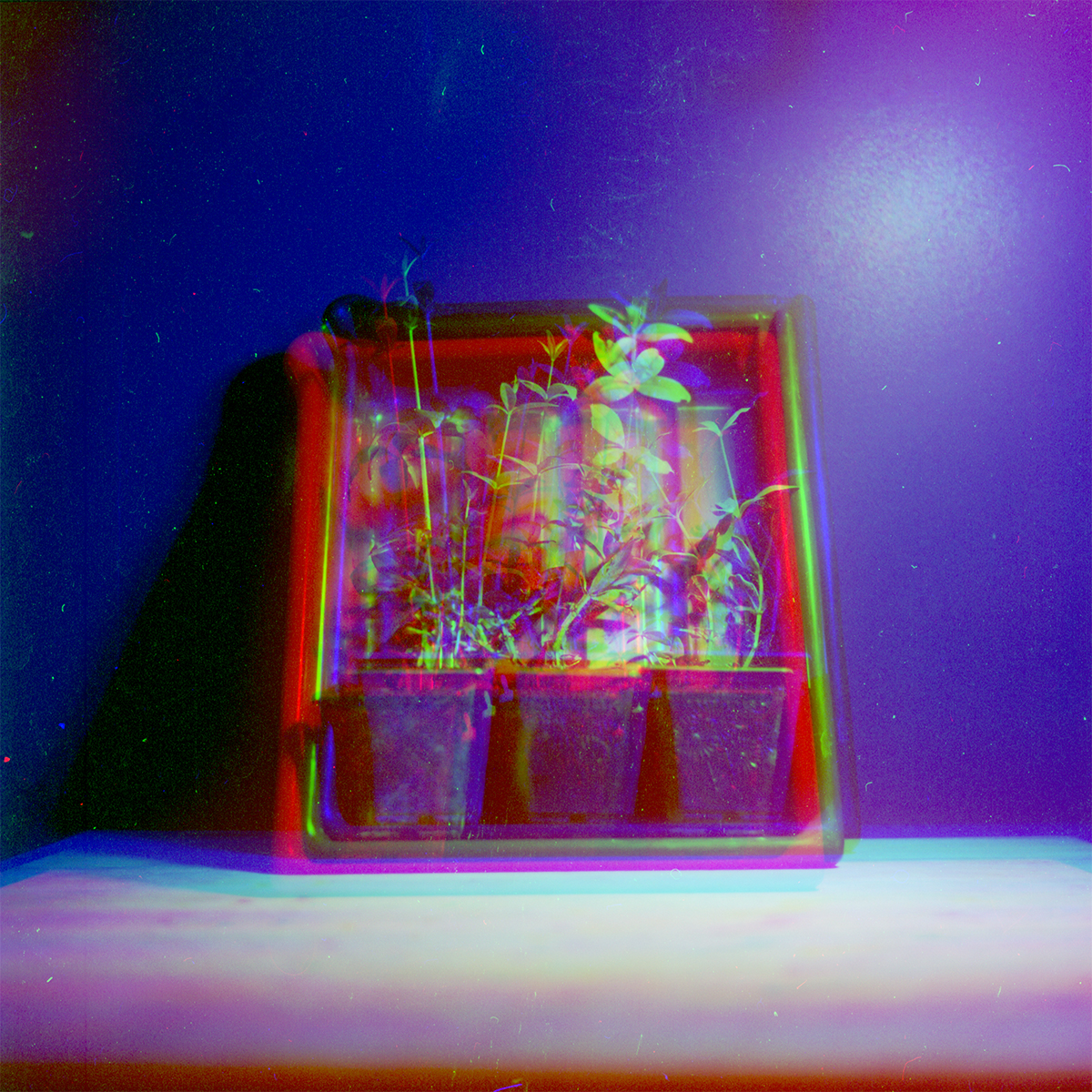

For its second iteration, Cabinet Cultures: East London Ecologies brought together Queen Mary University of London student representatives, artists, and academics to explore the institution's surrounding ecologies and histories through three vegetal strands across three modified IKEA ÅKERBÄR greenhouse units: ferns, medicinal plants and mosses. The project was made possible via funding and support from Queen Mary Students' Union and Queen Mary University of London's Sticky Campus Fund.

Fern species are highlighted as one of the catalysts for the IKEA greenhouse cabinet phenomena. IKEA ÅKERBÄR units are also modelled after Wardian cases, specialised containers developed in the 19th century to study living ferns within London amongst high air pollution as well as transport living plant material to and from colonies and Imperial centres. Wardian cases were invented by Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward, who was a physician by training, reflecting the Garrod building’s status as a medical teaching facility, where the exhibit took place.

Medicinal plants follow, echoing the 2023-24 Barts and the London Sustainability Officer and medical student Alexandre Duponcheele’s interest in expanding biodiversity knowledge amongst students and staff. This unit catalogues the Mile End canal banks’ diverse medicinal plant inhabitants and traces the boundary between interior and exterior domestic gardening.

Mosses inhabit the third unit coinciding with ongoing research conducted by artists and computer science postgraduate research students Nirit Binyamini Ben-Meir and Erin Robinson. Here the focus is on the ways in which technology and living mosses can be combined while demonstrating how these beings react to stimuli and changes to their environmental conditions (e.g. moisture and temperature change) in real time. Mosses are embedded within houseplant cultures as propagation and pot topping media.

Cabinet Cultures: Cultivating Aesthetic, Ecological, and Heritage Value in Human-Houseplant Relations, 2023

Cabinet Cultures is an interdisciplinary project reflecting on collective attitudes towards houseplants’ value by making visible research about their roles in our social and political lives.

In its first iteration at London's Garden Museum, the exhibit re-appropriated a trending DIY project that transforms glass IKEA display cabinets into indoor greenhouses. Originating on the social media platform Instagram, greenhouse cabinets have emerged as a staple in houseplant enthusiasts' homes. Further popularised by social media houseplant content creators (aka plantfluencers), the practice has come full circle with IKEA now flaunting faux flora in their cabinet marketing.

Recontextualising this trend foregrounds the many shapes, rationales, and aesthetics embedded within human-houseplant relationships. Whether viewing plants as beings we create emotional bonds with or as object-commodities to be bought and sold on a booming international market, the exhibit sought to capture these multiple relations embedded in houseplant culture(s). Utilising IKEA display cabinets, each encasement featured a different plant genus or family, each of which explored the multiple values and modes of 'planting'.

Cabinet Cultures' first iteration was co-curated between myself and sociologist and academic Giulia Carabelli, with contributions and support from content creator Emma Angold (Good Growing), botanical illustrator and eco-conceptual artist Sarah Gardner, and the Garden Museum. The project was financed through the Queen Mary, University of London Humanities and Social Sciences Collaboration and Strategic Impact Fund.

Madder Array (ongoing since 2022)

Lest the Breed Should Become Extinct (After Perkin, 1876), (Artist’s Proof, Edition TBD), 2024

This print depicts Butler’s Green (Wembley, northwest London) in gum diazo using screen printing chemistry to produce full-(water)colour prints, replacing dichromate salts. Captured with RGB vegetal colour separation filters onto film, it is part of the ongoing Madder Array project combining eco/materialist photography, industrial (Imperial/colonial) histories, and care for rose madder to unpick photographic dyes' social, economic, and political lives. The site is the last remnant of Sudbury Common, opposite the now-demolished home of Victorian industrialist William Perkin, The Chestnuts. In British Imperial history, Perkin is credited as 'discovering' synthetic dyes while attempting to synthesise quinine to treat malaria, leading to the British commercialisation of alizarin—madder's principal colourant. Alongside two German chemists who produced a similar process (and patented it one day before Perkin in 1869), these actions would lead nearly directly to the collapse of all madder agricultural markets globally, many of which were already subjugated under European colonial rule. In 1876, Perkin planted madder on the green, remarking 'lest the breed should become extinct'.

Madder Array: Plant Portraits, 2024

Madder Array: Plant Portraits was a participatory project that took place at the South London Botanical Institute (SLBI). Taking its title from a recent exhibit at London’s Garden Museum entitled Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits, the concept of a plant portrait refers to Freud practicing capturing the individual character of the plants he painted. The goal of the workshop was to take this idea forward, introducing participants to Rubia tinctorum (rose madder) plants in the context of my practice's investigation into the plants' role in colour photographic history's dominant narrative, and how we might 'see' otherwise by collaborating with the plant in photographic production. During the event, participants photographed rose madder plants through a rose madder colour separation filter onto medium format film. They then contact printed their negatives in the gum diazo process, which used madder lake watercolour as the pigment.

This project was funded via a Queen Mary University of London Centre for Public Engagement Large Grant organised by Giulia Carabelli and Elyssa Livergant (SLBI Director). Special thanks to Kimberley Dixon for taking part and assistance on the day!

Madder Array: Part I, 2022

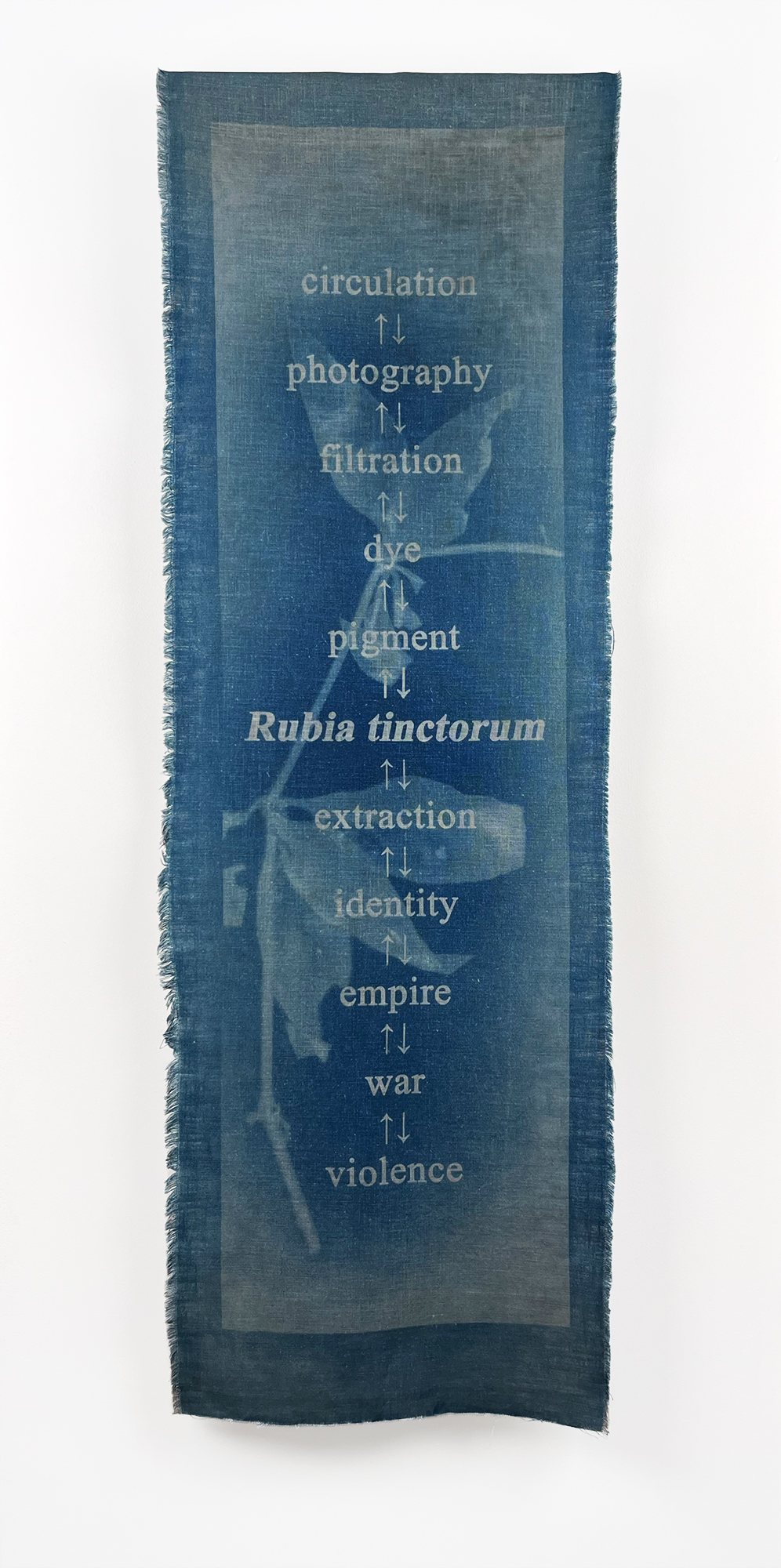

Madder Array: Part I presented an initial meditation on Rubia tinctorum, or rose madder, as a red photographic filter. Madder has a complex historical lineage, implemented as medicine, fibre dye, and paint pigment. Crucially, it was the key ingredient in the colouring of military uniforms for the British Empire (red coats).

The use of the word array in the exhibition’s title had three meanings: a formation of assemblages, a process of dressing, and as a continuing object within digital photography (describing the synthetic RGB dyes embedded in camera sensors).

Madder Array: Part I presented photographic objects in an initial exploration and examination of Rubia tinctorum’s extractive history, questioning how we might re-think gardening with the plant as a decolonising process in photographic image-making.

Throughout 2022, I began working with plant-based pigments in order to produce a series of red, green, and blue colour separation filters as a means to explore colour as a link between gardening and analogue photography — particularly plants from which natural dyes can be extracted. Current processes involving plant-based photography and colour (chlorophyll prints, anthotypes) rely on the lack of lightfast characteristics in plant material in order to create colour imagery through bleaching. However, plants desirable for natural dyes/extracts produce extractable pigments that are explicitly lightfast.

The purpose of this research is to find a way to produce plant-based colour RGB image separations (and conversely CMY print separations) using black and white film, particularly in the context of The Sustainable Darkroom organisation's research into plant-based developers. Further, this research enacts a conceptual link between it and plant material by offering an opportunity to connect with dye plants’ materiality via colour perception in an alternative medium to painting or textile art.

A special thanks to The Sustainable Dakroom founders Hannah Fletcher, Alice Cazenav, and Edd Carr for enabling the initial project, Screw Gallery for exhibiting the works, East Street Arts for hosting, Algy Kazlauciunas and Mohammed Asaf at Leeds University's Colour Science Analytical Lab for running Spectral Reflectance tests, and the Genesis Foundation for funding.

Demo Day at the Botanist's Conservatory, 2021

While attending the LABVERDE residency, my home was in the process of being renovated. During the demolition, multiple layers of wallpaper were uncovered, which inspired me to begin cross-referencing the dates plants were recorded with the production of British wallpapers featuring tropical and subtropical plants. For example, the Philodendron pedatum was first published in the UK after being categorised in 1841 by British botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker. Many of the wallpapers featured in these works were produced during the same time period and coincide with the British expedition of the HMS Beagle in 1832, and the HMS Erebus and Terror in 1839 (all of which made trips to Brazil during their journeys).

The series of works deploy reproduced wallpapers from English Heritage’s and The National Trust’s wallpaper archives. Each wallpaper was pasted and layered onto a small section plastered wallboard, acting as a kind of stage set, upon which Philodendra shadows were projected. The work plays with the scale of the shadow relative to the wallpaper, producing a kind of monstrous form via shadow puppetry. The resulting collaged backdrop is frozen in time as a new archived form before being printed back true-to-life scale on plastered wallboard and framed with reclaimed floorboards from my home.

The resulting scenes of shadow play reflect on what gets left out in the process of updating domestic spaces — using questions around surface and materiality to problematise how the imaginaries created using wallpaper or murals affect the stories we tell and are told about the histories and environments of the species depicted.

William Morris and Roberto Burle Marx on Holiday at Charleston House, 2021

William Morris and Roberto Burle Marx on Holiday at Charleston House is a wallpaper pattern that draws influence from my lived experience, artistic practice, and research into visual imaginaries of tropical and subtropical plants. While trekking through the Amazon rainforest in 2019, I learned about the symbiotic relationships between Philodendron species and different species of scarab beetles and ants. This wallpaper pattern works to bring these ideas into the domestic sphere, asking how new interspecies relations might be possible between houseplants such as Philodendron, and scarab beetles such as Geotrupes mutator (violet dor beetle). The violet dor beetle makes an appearance within the wallpaper on the Philodendron flowers (or inflorescences). Such interspecies possibilities are relevant as recent reports by Natural England and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee have highlighted the increasing decline of UK Dung beetles, whose ecological niches provide vital ecosystem services such as reducing pasture fouling and soil compaction.

The title and aesthetics of the wallpaper was inspired by a previous artist-in-residence period at Charleston House, the historic home of the Bloomsbury Group; as well as the practices of British textile designer William Morris and Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. As tropical wallpapers continue to gain popularity within contemporary interior design, this project asks what conversations might take place between these two practitioners in the context of Charleston House in the aftermath of botanical expedition and extraction.

Propagations, 2020

The Propagation series depicts my ongoing interest in domestic horticulture as it relates to wider debates and contentions about tropical and subtropical landscapes; histories of expedition, extraction, and empire; and the booming global houseplant economy. A particular species is depicted in this emerging project: the Philodendron pedatum. Endemic to most of Northern Brazil. Philodendra more widely have been popular houseplants for decades, many of which were brought back to the United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Austria as part of expeditions the 19th century. Contemporary dissemination of these plants is largely a result of large-scale growing operations in Southeast Asia. The plants, reproduced through propagation and tissue culture, find their way into homes all over the globe. I am interested in how these companions might be taken for granted, and how our relationship to them can be complicated through processes of domestic propagation and printmaking. The works depict single leaves of a Philodendron pedatum plant, which grows as one continuous vine. Each leaf is produced by a node, and when cut, holds the potential to form new roots and new growth; thereby vining anew. Often this original leaf dies back as the plant consumes energy.

Each print presents this singular leaf reproduced at a true-to-life scale using the cyanotype process, complicated by the act of exposing onto conservation paper, followed by the process of chine-collé in order to attach the cyanotype object onto a support paper. This process mirrors the same practice of conservationists working with botanical ‘specimens’, whereby often conservation paper is soaked in gelatine coupled with backing paper in order to form a support, fixing the plant matter into place. This act of considering matter and materiality through conservation practice is a way to think critically about the way botanical collections are formed and employed, as well as brings what is often hidden out of view in institutions into the public sphere.

LABVERDE, 2019

LABVERDE is a short-term residency programme for artists working around environmental concerns. Its unique programming includes participants from all over the world who come together for an intense period of learning across treks, scientific lectures and talks by curators and other participants, artistic interventions, river travels, and a professional relationship building. The programme’s aim was to bring together knowledges and practices between artists and natural scientists, embedded within the context of the Amazon River and rainforest. Examples of natural science influence included a botanist who helped guide us in the first half of the trip, a series of talks on topics such as dendrochronology and the area’s environmental history.

For the past couple of years, I, alongside many others, have taken part in the resurgence in popularity of houseplants. Earlier in the summer before the programme, I moved from a one-bed flat to a three-bed semi-detached house that had not been updated since the 1970s. I began purchasing many more plants to fill the space, which involved a lot of further research into the care of these different plants in the context of an interior space. Through this action, I came to realise that many of the plants sold a houseplants are tropical and subtropical species. This was further compounded by seeing many of the same species I have in my home used to adorn the public spaces in Manaus, the city in which LABVERDE is based. This hints at an interesting global network of plants as commodities — some plants that are native to Brazil are not used in landscaping, and instead others are imported from elsewhere. And conversely, the same might be said for other regions of the world.

The displayed video work above depicts two different scenes of domestication but two different species. In one, a human prepares node cuttings of plants for propagation. In the other, displayed split-screen is an ant garden in the rainforest.

Ant gardens present interspecies mutualism through arrangements with various species of epiphytic plants, including those in the Philodendron genus. Ants create a structure of organic matter, roots, and other debris from which the plant grows. The plant benefits from the structure of the nest for support, nutrients, and moisture; while the ants benefit from sugar secretions from the plant. The ants add the added benefit of security to the plant by attacking herbaceous predators. The short scene offers a reflection on two different gardening practices between species while foregrounding the sound of ant’s protecting their habitat from a human encounter (herein gathering sound recording).

But why care about houseplants in the context of this residency programme? My interest was piqued purely on a base level of curiosity as to whether I might see any of my plants potted back at home growing unmanaged in any areas of the sites we would visit. And to my complete surprise, this was indeed the case. The more I spent reflecting on these circumstances while experiencing the programme, the more I began to examine my perhaps lack of criticality in keeping houseplants. Often people criticise taking animals from the wild to look after in their homes (e.g. tropical fish), but the same is much less often said for plants. I began to ask what it means to extract a botanical species from its native habitat: what are the environmental impacts? How do those who live in that environment relate to those plants? What more-than-human narratives and histories become lost through the practice of cultivation? How can the aesthetics surrounding houseplants be conceived of as a new sort of exoticism?

While such questions are perhaps overtly critical, I think some celebratory enquiry may be had too. For example, what kinds of new relationships are being formed between humans and plants put into new domestic environments? How do humans and plants domesticate one another? What kinds of knowledge is being passed between plants from different geographies? What other kinds of species are the plants interacting with? What new forms of botanical research may be had in the unique environment varied domestic spaces afford? What sort of value typology might be construed?

Prospect for the More-Than-Human, 2018

These works were produced with support from the 2018 diep~haven festival.

Nonhuman Care: A series of Speculative Gestures, 2017

Towards A Photographic Hauntology, 2017

Liminal Banks, 2017

Irregular Captures, 2015

Analogue Self-Portrait of a Digital Camera, 2015

About

I am an American-British (b.1993) artist-researcher and educator situated between London, UK and the American South Atlantic. Embedded within discourses around materiality, my practice explores the intersections between place, the photographic, and care in more-than-human worlds. Two primary strands of enquiry include companion relations with (sub)tropical flora and gelatinous zooplankton. Beyond these core aims, I also regularly teach within UK higher education, as well as engage with policy and practice, focusing on postgraduate student voice and research culture.

I hold Advance HE Associate Fellowship, an MA from the School of Geography, Queen Mary University of London, an MFA from the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, and a BFA from the College of the Arts, University of Florida. I am also an alumnus of the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art (2016) and LABVERDE (2019). Recent outputs include contributing to Eroding Forms (published by Ephemere in collaboration with Alternative Processes), The Active Image: Political Ecologies & Photographic Agency, Create Centre, Bristol, and Cabinet Cultures: Cultivating Aesthetic, Ecological, and Heritage Value in Human-Houseplant Relations, Garden Museum, London. My work has also been screened at The Showroom and Bloomsbury Theatre. My written work has been published in The Conversation, Wonkhe, and in academic presses. More widely, my practice has been supported by the Genesis Foundation, the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), and Arts Council England.

Previously, I have held posts as a Research Fellow in the Department of Sociology, Politics, and International Relations, Queen Mary University of London; Visiting Researcher and Scholar in the Lamar Dodd School of Art, University of Georgia; Artist-in-Residence at The Sustainable Darkroom; and Research and Teaching Fellow in printmaking at City and Guilds of London Art School. I also completed a tenure as a Sabbatical Officer within the Queen Mary Students' Union, where I remained a trustee through 2024. Currently, I am writing up my PhD project in the School of Society and Environment at Queen Mary University of London under the supervision of Catherine Nash and Kathryn Yusoff. My doctoral research, entitled Gone Jellyballing, examines historical and contemporary practices of producing and consuming gelatinous life. Funded via a Queen Mary Research Studentship, my project focuses on the United States' only operational jellyfish fishery, which is in the state of Georgia extracting Atlantic cannonball jellyfish (Stomolophus meleagris). I am due to complete summer 2026 and intend to publish this research as an academic monograph.

Outside of my solo work, I regularly collaborate with sociologist and academic Giulia Carabelli (@careforplants). Together, we co-curate The Plant Forum, an interdisciplinary research group within Queen Mary University of London's Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, where we recently collaborated with plant studies practitioner and academic Prue Gibson to facilitate The Dose, a cross-hemisphere virtual symposium. Alongside geographer Franklin Ginn, we also have a new edited volume in critical plant studies under contract with Bloomsbury Academic.

Across my practice, I have utilised alternative photographic processes for over fifteen years and regularly organise and/or facilitate workshops, talks, and other educational events. For half of that period, I have grown copious numbers of (sub)tropical plants, namely Philodendron, Monstera, and Alocasia. I also have extensive experience successfully applying for and managing small (up to £2,500) and medium (up to £10,000) grants across research, higher education, and public engagement. If you require assistance in any of these areas, particularly if you are a student or students' union, please don't hesitate to reach out.